A BRIEF COMPILATION OF THE MAJOR POINTS OF THE CATALPA RESCUE STORY by Paul T. Meagher

The bare bones of the story of the Catalpa Rescue is familiar to most members of the Friendly Sons. It tells of the escape, on 18 April, 1876, of six Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) prisoners from the Convict Establishment (now Fremantle Prison) in the British Penal Colony of Western Australia. It describes their successful evasion of recapture aboard a New Bedford whaling bark, Catalpa, and their triumphant reception in the USA and subsequent freedom.

The bare bones of the story of the Catalpa Rescue is familiar to most members of the Friendly Sons. It tells of the escape, on 18 April, 1876, of six Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) prisoners from the Convict Establishment (now Fremantle Prison) in the British Penal Colony of Western Australia. It describes their successful evasion of recapture aboard a New Bedford whaling bark, Catalpa, and their triumphant reception in the USA and subsequent freedom.

Background:

The full story of why the six prisoners were singled out for rescue from among the hundreds of Irish republican prisoners in Australia, and the reason they were chosen in the first place by the British for the harshest sentences, are central to this story.

During the years 1865 to 1867, the British in Ireland became concerned at the intelligence being collected by their informers among the Irish, of rebel activism in the British Army stationed in Ireland. It was estimated that of 26,000 British Army troops garrisoned there, over 8,000 were sworn members of the IRB, known familiarly as “the Fenians”. The name derives from a pre- Christian warrior society in ancient Ireland. In the United States, the movement was known as “Clann na Gael” Gaelic for the tribe or extended family of native Irish. In England, a further 15,000 soldiers were believed to be sworn Fenians serving in the British Army. The purpose of Army service was largely to gain battle experience to be used in armed rebellion against British rule in Ireland.

Seven high profile soldiers in Ireland were arrested, all serving in, or deserters from, the Army. As so often happened in Irish history, they had been betrayed by fellow Irishmen — informers. Those taken included:

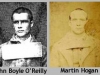

John Boyle O’Reilly, Trooper, 10th Hussars

Martin Hogan, Trooper, 5th Royal Dragoon Guards

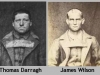

James Wilson, Trooper, 5th Royal Dragoon Guards

Thomas Hassett, Private, 24th Regiment of Foot

Michael Harrington, Private, 61st Regiment of Foot

Robert Cranston, Private, 61st Regiment of Foot

Thomas Darragh, Sergeant Major, 2nd (Queen’s) Regiment of Foot

Following their arrest, these men were tried and convicted, not for sedition or rebellion but for the infinitely more serious charge of treason — being British soldiers — carrying the penalty of death by hanging. Victoria, Queen of England, graciously commuted the sentences to transportation and penal servitude for life in the Penal Colonies, arguably a sentence of equal or greater harshness.

All of these men, together with more than 50 others, were sent aboard the convict ship Hougoumont which carried them to Western Australia – the last political prisoners Britain would ever transport to Australia. On instructions from the government, the seven prisoners of our story were made the objects of persecution by warders and guards throughout the three-month voyage. On arrival in Western Australia they were incarcerated in the Convict Establishment a brutal, almost medieval, jail and assigned to the most rigorous work details, quarrying stone, cutting timber, building roads, and other backbreaking labor in the suffocating temperatures.

Australia:

Escape was thought impossible. Any attempt was punishable by solitary confinement, reduced rations, extension of sentence, flogging, or even death. Any would-be escapee who got away from a road gang faced endless desert and bush on the one hand or the vast ocean on the other. The bush was infested with venomous snakes, spiders and insects. Water was scarce, and unfamiliar fruits and berries might be poisonous. The ocean teemed with enormous white sharks. Escaped prisoners were tracked by implacable aboriginal hunters who could follow spoor through forest, across barren desert and even over rock. The only likely escape was death.

Nevertheless, in 1869, two years after their arrival John Boyle O’Reilly made a daring escape aboard the American whaling ship Gazelle, with help from a local Catholic priest, Father Patrick McCabe and sympathetic parishioners in Australia. He was also helped by an officer of the ship, a seasoned New Bedford whaler named Henry Hathaway who shared his cabin space with the escaped prisoner on the homeward-bound voyage. They became and remained firm friends. O’Reilly settled in the United States and made a career as a journalist, poet and later editor of the Boston Pilot, a Catholic newspaper.

News of O’Reilly’s escape sent shock-waves through the authorities of the “escape-proof” penal colony. His fellow prisoners were elated at the news that the prison was breakable. In June 1870, Thomas Hassett made a run for freedom and remained at large, hidden by sympathizers, for almost a full year. He was eventually caught trying to stow away on an American vessel, the Southern Belle, and sentenced to six months solitary confinement and three years in the most brutal work gang in the Colony, a sentence from which his health never fully recovered.

America:

Meanwhile, in the United States, O’Reilly was tormented by guilt at his freedom while his comrades suffered silently and apparently forgotten to rot in Fremantle. He exhorted a fellow exile and Clann na Gael member, John Devoy, to urge the board of the Clann to consider helping financially and organizationally to mount an escape attempt similar to his own for the “Fremantle Six”.

In July 1874, sixty Clann delegates from all over the USA met with Devoy who implored them to help the Fenian prisoners. At a private session of the 5-member board of the organization, Devoy used moving letters from Martin Hogan and from James Wilson, writing as “a voice from the tomb” as the basis for an impassioned speech on the prisoners’ behalf. The letters stunned the board and they cautiously endorsed his daring plan to mount a rescue by sea. The first task was to raise funds. Copies of both letters and a rough outline of a rescue scheme were sent to the eighty-six branches of Clann na Gael throughout the United States. Donations poured in but not enough to purchase and outfit an armed ship, as originally envisioned.

An alternative plan was devised, using a leased or purchased whaling ship — logically from the premier whaling city of New Bedford — and serious preparations begun. First to be approached outside the Clann was the same Henry Hathaway who had helped O’Reilly escape. Hathaway was now a Captain of Police in New Bedford! Nonetheless, Hathaway was delighted to help his friend O’Reilly and made suggestions based on sound business understanding of ways to finance a voyage to Western Australia, in the merciful rescue of patriots opposed to the British Empire, still regarded as the old enemy by many US citizens. There was also lingering but quiet Federal rancor, in Congress and the Presidency of U.S. Grant, at Britain for providing aid on the high seas to the Confederacy during the recent War between the States.

Following Hathaway’s advice, they began to search for an experienced whaling agent who could help underwrite some of the costs of outfitting a vessel and who understood the filing of ship’s papers with Customs along with the countless other details of ship management. In exchange, he would receive a substantial share of the profits, if any, from the voyage. Hathaway recommended John T. Richardson, a local Quaker, as agent who in turn recommended as trustworthy Captain, George Smith Anthony, his son-in-law.

Captain Anthony, although he had no ties of blood or kin to Ireland, had agreed to the terms of his hire by the Clann. He was to sail a whaling ship, fitted for sea, and to keep a pretense, at least, of whaling while navigating to a rendezvous off the coast of Australia. There he would pick up some men from a small boat and return with them to the US, avoiding contact with British men-of-war throughout. His great-grandson Jim Ryan later said “It was never about money or even adventure … my great-grandfather said … ‘It was the right thing to do’ ”.

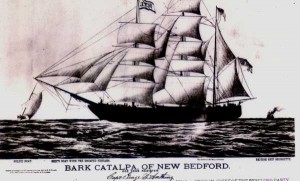

A three-masted whaling bark, Catalpa, was bought for $5,200 and a crew was recruited by the Captain. On 29 April 1875, Catalpa sailed from New Bedford across the Atlantic to the Azores, then south along the coast of West Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean to Western Australia. Along the way some whales were successfully hunted and rendered into barrels of oil as income to be set against the expense of the voyage. Nevertheless, Catalpa had fallen behind her anticipated schedule due to problems with the ship’s chronometer and consequent navigation. There was also storm damage, including loss of her foremast. Eleven months after her departure from New Bedford, she dropped anchor at Bunbury, some 50 miles south of Fremantle, on 27 March 1876.

Implementation:

Meanwhile, two Clann agents, John Breslin and Tom Desmond had arrived in Western Australia to prepare the local ground for the escape attempt. This included recruiting local sympathizers to cut telegraph lines at the time of the escape to hamper communications and pursuit. Breslin successfully masqueraded as a wealthy American investor by the name of James Collins, entrepreneur. Among others, Breslin duped the Governor of Western Australia, Sir William Cleaver Robinson, who hosted him on a conducted tour of “the Establishment”. Breslin reported that the prison was “very secure and well-guarded”, indicating that he would have to find a way to launch the escape when each of the six was outside the walls. This was a tough proposition, as all except one was now assigned to work within the prison walls.

Through Father McCabe, still the local parish priest, Breslin was able to let Wilson know secretly that a rescue was planned, but no more. It was up to Wilson to ensure that the Fenian prisoners were on their best behaviour, as anyone in solitary would have no chance of escape, to be left behind probably for ever. Breslin urged Wilson meanwhile to have the prisoners try and get assignment to outside work details in preparation for the day yet to be named. A fellow Fenian, John King, later joined Breslin in Fremantle posing as a gold-mining investor named “George Jones”, bringing much-needed funds to help Breslin maintain his necessarily luxurious lifestyle.

Through informers in Ireland and England, the British authorities had wind of a vague escape attempt planned from Dublin but had little concrete detail. They had no idea that another plan had been formulated in America and was awaiting only the arrival of a whale ship. There were actually two undercover Fenians in Fremantle, Dennis McCarthy and John Walsh, travelling as “Alfred Dixon” and “Henry Hopkins”. Unknown to Breslin, they had been sent from Ireland to carry out a less well-thought out plan. Each group thought the other was made up of British spies! They eventually reconciled and agreed to work together from the Devoy/Breslin plan. All that remained was to get news of the long overdue Catalpa. On the morning of 29 March 1876, Breslin at last saw on the bulletin board of the Fremantle telegraph Office notice of the arrival at Bunbury of the whale ship. Wilson was alerted and told to prepare his comrades for deliverance — or possible death! Breslin went to Bunbury and finally met with Captain Anthony.

Desolate Rockingham Beach, some 20 miles south of Fremantle, had been chosen by Breslin as the place of departure for the escapees. It was picked from among the several beaches reconnoitered by Breslin for its firm packed sand, unlike the deep soft powdery sand and wide beaches unsuitable for moving at speed toward a small boat and freedom. After several false starts, Captain Anthony was instructed to have Catalpa ten to twelve miles offshore from Rockingham on Easter Monday, 18 April 1876 and to have a whaleboat waiting on the beach before first light. If the whaleboat or the ship carrying escaped felons were to be apprehended in territorial waters by the Royal Navy, all aboard would be sent to Fremantle Jail or to their eternal reward. The whaleboat, with Captain Anthony at the tiller, alternately rowed and sailed to shore the many miles from Catalpa on the night of Easter Sunday.

Escape and evasion:

Early on Easter Monday, a local holiday, using various pretexts, the six prisoners who had given their jailers no cause for suspicion made their separate ways to a pre-arranged rendezvous with Breslin and Desmond. The two were mounted each on a four-wheeled trap drawn by reliable horses. Each trap could carry three prisoners in a headlong dash toward Rockingham Beach. Rifles, pistols and civilian clothing had been provided for the escapees who were determined to sell their one chance of freedom dearly, indeed, should they be discovered.

Arriving at the whaleboat after a two hour gallop, all the men, their weapons and gear, piled aboard. Under the weight of sixteen men, the boat pulled sluggishly away from shore. Progress was further hampered by an onshore wind and heavy black clouds could be seen gathering to westward. When the boat was not much more than half a mile from shore, prison guards, Territorial Mounted Police and aboriginal trackers were seen pouring on to the beach. Out of rifle range, the frightened crew began to put increased distance between themselves and their pursuers. Catalpa was many miles offshore, with a gale approaching from dead ahead of the whaleboat.

Previously cut telegraph wires were soon repaired and pursuit stepped up. By process of elimination, the bark Catalpa was identified as the only American whaler in the vicinity likely to be the escape vessel. The Royal Navy was alerted. The steamer S.S. Georgette was commandeered by the Governor and commissioned for the chase. Armed with a twelve pounder cannon and Royal Marines, it also took aboard a heavily armed detachment of Territorial Police. The order was telegraphed to all Royal Naval Stations and ports in Australia “to detain, by force if necessary, the American whaling bark Catalpa, George Anthony, Master. Arrest said Anthony, his officers and crew, and any passengers who may be aboard”.

After 28 hours in the open whaleboat, under rainswept skies and heavy winds, and having perilously evaded both the Georgette and a Police cutter, Captain Anthony, his exhausted crew and the soaked and frightened Fenians were able to board the Catalpa. The next morning, following a windless night with no perceptible movement of the ship, the men awoke at daybreak to find Georgette bearing down on them under a full head of steam. Irishmen and crewmen alike armed themselves as best they could and prepared to repel boarders. The American ensign was hoisted to the highest part of the mainmast. Just then, a favourable wind to westward picked up and Catalpa began to make headway. Captain Stone of Georgette ordered Catalpa to heave to. Anthony ignored the signal. Georgette’s twelve pounder put a shot across the bow of Catalpa but the whaler, with all sail set defiantly proceeded to the west and the open ocean. Responding to further frustrated threats from Captain Stone, Anthony shouted “If you fire on me, I warn you that you are firing on the American flag”. Despite his orders, Stone was reluctant to provoke an international incident and Catalpa bore away. She continued westward and made landfall in New York harbor on 19 August 1876.

Aftermath:

Captain Anthony sailed onward to New Bedford having dropped his passengers off to a riotous reception. In New Bedford, Captain Anthony was met by his family and hundreds of cheering supporters at the dock. He was greeted as a hero and a gala reception in his honour was held at New Bedford’s Liberty Hall. The guest speaker was John Boyle O’Reilly. In February 1877, Clann na Gael settled with Captain Anthony and his crew for their part in the rescue. Cash payments in line with “share of voyage” plus a “gratuity for rescue” were made in proportion to all. In addition, the Clann donated Catalpa as an outright gift to Captain Anthony, John Richardson and Henry Hathaway. The ship was sold and finished her days abandoned and burned on a beach in Belize, British Honduras, in the 1880s. Captain Anthony could never again command a ship on the high seas as he would be subject to arrest in any port where the Royal navy docked. This was at a time when “the sun never set on the British Empire”. Captain Anthony died of pneumonia, aged 69, on 22 May 1913.

For Clann na Gael and the rescued “Fremantle Six” the success of the mission and the resulting publicity meant membership, funding and goodwill mushroomed.

John Boyle O’Reilly never actually joined Clann na Gael, although without his example and support the voyage of Catalpa would doubtless never have occurred. O’Reilly died peacefully at his home in Hull, Massachusetts, in 1890.

John Devoy remained among the leadership of Clann na Gael his entire life as it funneled money and arms to Ireland for the emerging Gaelic League and Sinn Fein and ultimately the Easter Rising of 1916, which brought about a free Irish Republic.

Robert Cranston married soon after his arrival in New York and settled there, working for the leadership of the Clann.

Martin Hogan moved to Chicago, also remaining active in Fenian affairs. He had trouble adjusting to his new life after so many years in prison and reportedly may have developed a drinking problem.

Michael Harrington and Thomas Hassett passed away in the early 1890s, their health ruined in prison.

Thomas Darragh attended a reunion of survivors of Fremantle Jail in Philadelphia in 1896. Martin Hogan and Robert Cranston were there too. The guest of honour was Captain Anthony who presented to Clann na Gael the American flag which he had flown from the mainmast of Catalpa, twenty years earlier. Over four thousand men, women and children rose to their feet as “the Stars and Stripes were unfurled to the breeze”.

Tom Desmond went on to serve as the elected Sheriff of San Francisco, remaining immersed in Clann affairs until his death from natural causes in October 1910.

Father Patrick McCabe left Australia several years after the rescue and became a parish priest in Minnesota until his death in 1890.

James Wilson married and raised a family in Rhode Island, although he always suffered from heart disease. In 1920, Eamon De Valera, future President of the Irish Republic, on a tour of the United States in late June, met in Pawtucket Rhode Island with eighty-one-year-old James Wilson. Despite his heart problems, Wilson lived long enough to see Ireland on the verge of an independent Free State. He died in 1920, one year before independence. The man whose letter may have started it all, “the Voice from the Tomb” was no more.

De Valera made one last stop on his tour of New England. Flanked by the widow Emma Richardson Anthony and Captain Henry Hathaway, De Valera laid a wreath and the Irish tricolour on the grave of Captain George Smith Anthony, a quiet hero who did what he did “because it was the right thing to do”.

Paul T. Meagher